Cultural group selection for group-enthusiast physicists

Published at Jul 5, 2024

What explains large-scale collaboration among unrelated individuals? For anthropologists, It is a mystery because reciprocity at that scale does not follow from our most beloved models in biology, aka evolutionary game theory and population genetic models. To solve this cooperation problem, they recast inclusive fitness theory into cultural group selection (CGS). Building on cultural evolution theory, they assert that (some) cultural behaviors have evolved because they provide group-level benefits, and these are crucial in explaining the evolutionary success of humans. What do they mean by that?

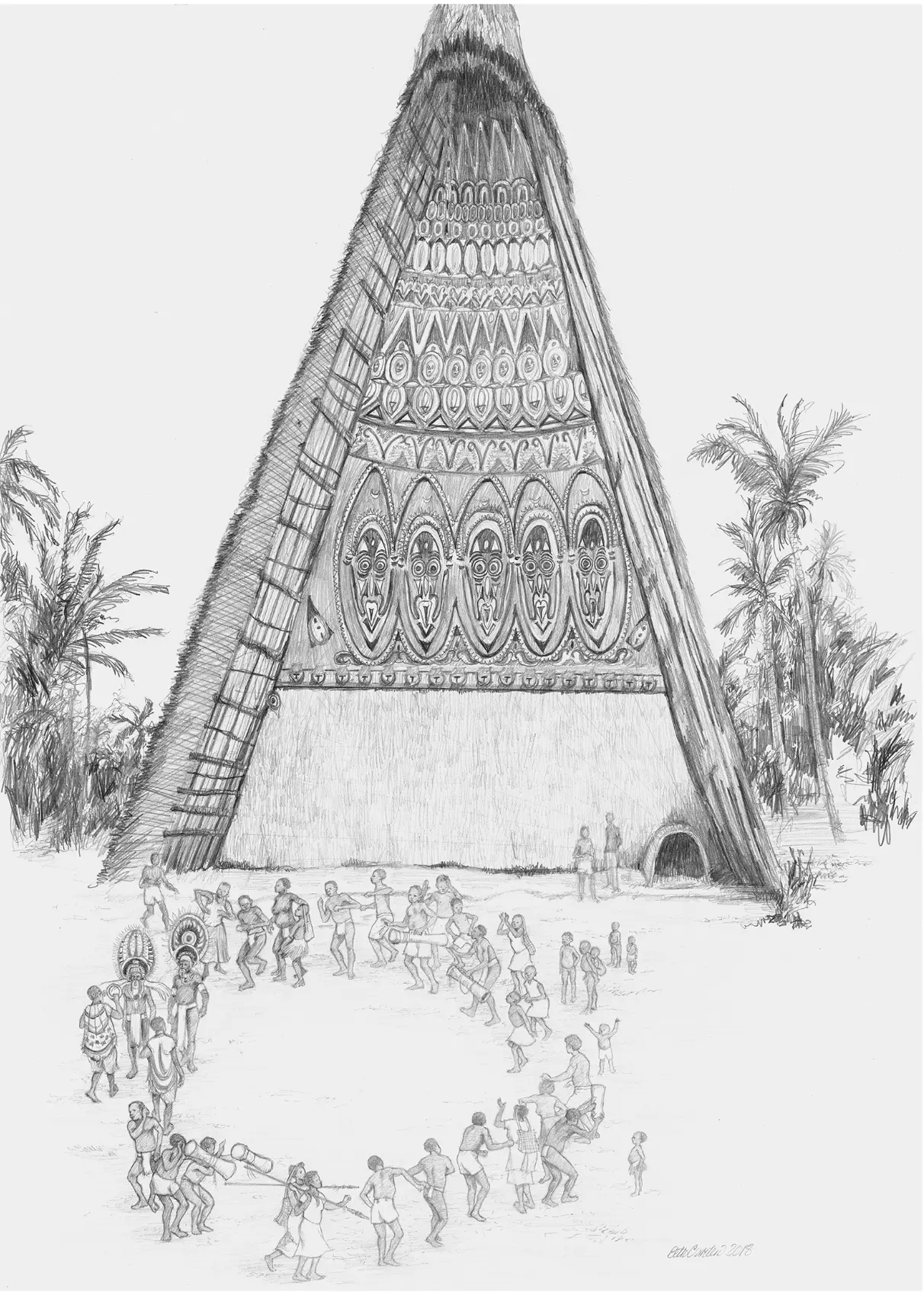

First, what are group-level cultural traits. In his book on the The WEIRDest People in the World (that’s us Westerners), Joe Henrich tells the story of how Ilahita, a traditional society from New Guinea, got big for that time and place (≫300 people). How? A collection of stories, myths, and rites of terror that have facilitated interactions among distantly related households.

For instance, every household raises pigs, but they find that eating their own pigs is disgusting because it would be like eating one of their own’s kid. This means that groups must exchange pigs at communal ceremonies. Furthermore, those ceremonies involve rites of passage for boys to become men (meaning boys can marry, learn about secret ritual knowledge, and climb the political ladder). The catch is that those rites must be performed by an opposite ritual group, meaning your success isn’t solely dependent on your own group.

Once you start looking for organizational norms, there are more than you know. llahita’s best of includes infusing terrors in their rites of passages because the Tambaran gods demand it (including going out and killing men from enemy communities), undertaking large community works (with some music-making and synchronous dance involved), and finally the ability to punish people who are doing ritual performance wrong.

From a network perspective, the idea of exchanging pigs with other groups, arguably, make more sense at the level of groups than at node-level. This is about how groups should behave towards each other. Of course, this is ingrained in individual psychology; people choose to punish one another because they don’t do what the gods want or experience disgust at the thought of eating their own pig. But sometimes stories and behaviors can be best explained at group-level.

But where is the math showing that, physicists ask.

Cultural group selection, actually

CGS is rooted in population genetics. Population genetic models are all about keeping track of copies of different alleles that might increase or decrease fitness under the effect of natural selection. A key relationship (theorem? model?) in the field is the Price equation:

Recall from statistics that covariance takes different forms. It can be written as the average over the product of individual traits and fitness minus the product of their averages,

It can also be written with a cofficient regression,

, revealing how without variance in allele frequencies you cannot have selection.

Cultural evolutionists now make a bold move to natural selection could (in principle) favor group-level traits, even in the face of individual cost:

On the left, we represent a diploid individual, with its two set of genes that could be realized into one of two behaviors. In this world, we track the changes in individual allele frequency over generations, regardless of the population structure. On the right, we have two individuals as part of a group, each with a realized behavior. Below, we denote pig as the frequency of individual ᵢ with realized behavior, labeled S, in group g. Accordingly, wig refers the number of copies of that behavior in that group.

Cultural group selection is a multilevel selection framework, which means we can decompose the above into nested components.

= +

(General form of Price equation;

see Mcelreath & Boyd 2008 p.229 for a more detailed derivation)

This is the core of the multilevel selection idea of CGS. Basically, you can decompose the selection effect on behavior S across groups and individuals, looking at which part explains variance the most, as with something like ANOVA. Using the fact that we can write covariance such as , cultural evolutionists like to use the following, more practical form

(Showing the regression coefficient)

what really matters is the relative strenght of selection within and between groups. The two terms have inverse signs, meaning that when one goes up the other one needs to go down. In Boyd et al. 2016, their main sketch of quantitative evidence is actually in the form of

(Showing the regression coefficient)

where Fst is the fraction of total variance that is between groups, aka var(pg). The punchline should be clearer now,

Anthropologists argue that group-based cultural systems are like that.

Return to Ilahita

We briefly come back to Ilahita’s stories to clarify a few points about the scope of CGS, mechanisms, and levels of selection.

Beyond stories and rites of terrors, Henrich argues that Ilahita’s scaling up is due to intergroup competition among (39) clans.

Intergroup competition is hypothesized as a key driver of cultural group selection. For instance, violent conflict such as wars is a great way to preserve strong between-group competition (increasing pg) while maintaining conformity among your rank (reducing pig). Other mechanisms from cultural evolution theory further promote conditions for CGS to work, such as exhibiting preferentially learning from your peers (biased social learning; further reducing pig). We discuss in more depth the mechanism of CGS in another entry.

For fun and glory: the many lives of the Price’s equation

In a nutshell, we are thinking about the covariance between average group fitness and average group allele frequency.

I want more!

Cultural group selection is connected to the following topics in McElreath & Boyd’s book:

- Reciprocity and collective action (ch. 4.5)

- Altruistic punishment; second-order dilemma (punishing those who failed to punish; ch. 4.5.2). Second-order dilemma could be a nice use of adaptive higher-order interactions.

- More generally, n-person games (ch.4.5.1) and repeated interactions (ch. 4.1.1)

- Costly signal theory; what if people fake their intent (ch.5.1)

Some papers making use of CGS:

- Group Beneficial Norms Can Spread Rapidly in a Structured Population (Boyd & Richerson 2002)

- The co-evolution of individual behaviors and social institutions (Bowles et al. 2003)

- Collective action and the evolution of social norm internalization (Gavrilets & Richerson 2017)

- Reducing global inequality increases local cooperation: a simple model of group selection with a global externality (Safarzynska & Smaldino 2023)

Reviews of CGS:

In the next part of the series, we look at how CGS can relate to group-based master equations.